|

|

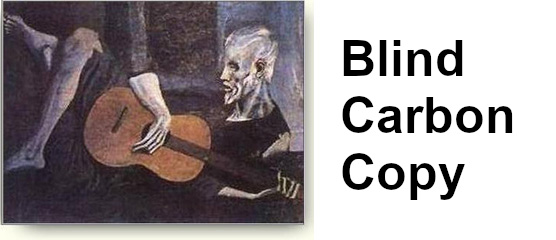

Fishing for Love by Blind Carbon Copy My old friend Mark Twain once said to me, "Jake (my moniker at the time), old boy, you may not appreciate just how lucky you are — you never have to look for love, it always seems to find you. For the rest of us, it ain't always so easy. Like you, I've always been considered a clever man, but if there's one thing I've learned, it's this — when you fish for love, bait with your heart, not your brain." He's often right, you know, but I wasn't always so smart — or so lucky in love, neither. I've lived a lot longer than most folks I know and had my share of success with the ladies. However, when I wasn't more than a sprout I admit to being uncomfortable around girls. I had a radar for sensing the life in a young woman long before she was close enough for me to smell the delicious perfume of her freshly starched cotton petticoats or the hint of vanilla she might've dabbed behind her ear. But as soon as she was close enough to see me, I sensed something else — a breathlessness, apprehension, maybe even fear. Then, mostly to calm myself, I'd start to play my banjo, sing a song — sometimes about the confusion I was feeling — until the apprehension seemed to melt away. She might stop to speak to me about the music, but there was always a line that never got crossed. I talked to Granny about this and she allowed as how it might be harder for me to find love owing to my inability to see what was right in front of my face. She had this friend lived up on the mountain who dabbled in the darker arts and she took me to see her — Widder Walker was her name as I recall. I sat on her straight-backed kitchen chair and she said, "It don't seem right messin' with someone God's teched like this. He must've had a reason to mark this boy and I can't say they won't be reaper cushions. But I swear by my dead husband, they'll be your reaper cushions — not mine." She spat in the fire, then set about concocting a potion from the contents of a number of jars and boxes around the room. She pounded the ingredients into a powder and the strong smell of old, dead fish filled my nostrils. She filled a small cloth pouch with the powder and hung it by a string around my neck. "Fishy," says I. "Two bits," says she. I count out the pennies from my pocket and she hurries Granny and me out the door as if we might suddenly change our minds. Now Granny, she always saw the best of everyone and she starts supposing how the Widder must know what she's on about with this fishy conjurin' of hers. She talks about salmon swimmin' upstream to where they was born so they can mate and die. I don't think I want to die just yet. I don't know what I want to do, but I feel like if I don't do it soon, I'll surely burst. I'm wondering what it is I'm to do with this fish potion. Do I put it in my drink? Give it to a girl? Leave it around my neck? I opt for the latter since it requires the least amount of effort on my part and, in spite of the strong fish smell, there is an underlying hint of something potent — like that first smell when you strike a wooden match. It makes me pull up my shoulders and walk a bit taller. As we come into town, Granny takes her leave of me, saying she's got to pick up something at Ike's. I reckon she's had about enough of that fish. I sit down on a bench outside and start pickin' my banjo and singing softly about how I feel. The next thing you know, I hear a voice — no radar warning. No sound of petticoats rustling, no hint of fresh starch or vanilla — just this delicate tinkling little voice coming at me through the fish smell. "Hello, she says. "That is a right pretty little tune, there. Kind of sad, though. Are you sad?" My heart is jumping out my throat and I reach for the pouch hanging around my neck. It's working, I'm thinking — I can hardly breathe, but I go on pickin' and I tell her it's one of my blue songs. The blue ones are always sad, I say and a tear runs down my cheek — though it must not be a tear of sadness, the way I'm beginning to feel with her so close. She brushes the tear away with her soft fingertips and kisses my cheek where it was. "Blue songs? How can songs have colors? Have you always been blind? How can you know about colors if you can't see." I tell her I don't know the colors, but I know the words for them and how people use them — certain words say how I feel better than others. Sad feels blue, I say. Angry is red. White is how I'm told I look but know deep down I ain't. "Do you make up these words yourself?" "Yep," I say. "The words are mine and the music. It's what I do." She says someone who can express such pure beauty out of sadness has a real gift. She says it's a shame I can't see the smile on her face and lifts my fingers to feel her upturned lips. Her face is smooth and round and I can feel the little curls dancing around her cheeks. I imagine they must look like the sunshine feels. Her lips are soft and thick and her tongue parts them, tasting the calluses on my fingertips. I shudder with a kind of electricity that makes parts of me stiffen with a mind to explore on their own this new territory. She brings her mouth to mine and kisses me and I think this must be what it's like to want to spawn and die. Then she asks if I'd like her to meet her later down by the river. Oh, yes! I say. She dashes off just as Granny comes out of Ike's calling for me to carry her parcel. I don't have much to say, but I know I must be all grins and I'm walking a foot off the ground, even though Granny's parcel is very, very heavy. She tells me I need to watch who I talk to, that people might get the wrong idea. She says that girl is known to be a bit fanciful in her ways — that she's been sent to England for her education and there's no telling what kind of wild habits she's picked up on the other side of the world. "The other side of the world! I'd love to go there and see for myself." (You see, I was born in Paris in 1789, but my papa brought me back to America before I was a year old. He was there learning how to do fancy French cooking so he could be the chef for Mr Jefferson when he came back to Monticello.) "Oh, Jackie, you don't know what you're saying, do you? There ain't no safe place out there for my blind baby boy. It's better you stay here in Virginia with your own kind." "I'm fifteen! And, what is my own kind, Granny? Seems like I don't rightly fit in with nobody. Even Papa doesn't want to be with me — he seems so angry all of the time. When I sing my songs, he always leaves the room." "It's because your voice is so like your mama's. It broke his heart to have to leave Paris after she died. He never planned to come back here to Mr Jefferson's place. If Marie hadn't been killed, you'd all be there still. He isn't angry with you, Jackie. He's just got too much anger for one man to hold — it's always going to spill out all over whoever he's with." "He should just sing it away. I wish I could have known my mama. I bet she was soft and pretty — like you, Granny." "Oh, thank you, boy. I was pretty once, or so I'm told. I never even saw a picture of Marie and James won't talk about her. Yer Aunt Sally says she was very smart — had ideas too big for a woman. S'pose that's what got her killed, right enough. She got stamped underfoot by a big crowd when they were storming that prison — the Bastille, it was called. Folks say things have really changed in France since then. No, you don't belong traipsing all over the world, Jackie." "Well, maybe I'll just go down by the river then." Granny took my arm. "You are growing up faster than I can make sense of! You do need a real papa sometimes, don't you? I wish he would talk to you about things. All I can say is, things are never as good, or as bad, as they seem. Life goes on. Sometimes we touch people and sometimes they touch us — and little bits of us and them get all mixed up and sometimes have a life of their own, whether we wanted it to happen or not. That's how you came to be here. Whether these things are a blessing is up to the folks who get left holding on at the end. I love you, boy, but I won't live forever. Somewhere along the line you'll need to learn to hold on by yourself. Just you be careful where you leave your bits." Later that day, I scrubbed myself up and wandered down to the river. On the path up from the bank, I met two fishermen who from their talk must have had a good morning. An omen, I thought as one of them spoke to me. "Hey, blind boy — you carrying bait in your pocket? You won't catch much with that banja, leastways not smellin' like that - pheeuuw!" I wasn't going to question my good fortune, so I just smiled and kept on the path to the river. The sun made the ground hot so I found a cool spot under a willow. I started to pick out a lively, happy tune on my banjo. A yellow one, bright and warm like the sun. Very soon I heard a giggle and the next thing she was sitting beside me, spreading her full skirt over the grass like a quilt on Granny's bed. She inched up close and leaned against my arm, feeling the vibrations from the banjo. She waited to speak until the song was finished — an eternity, it seemed. "Beautiful! Simply, beautiful. I am breathless — and what is your name, my talented friend? I'm Charlotte. My friends call me Lottie." "Charlotte is a name to grow into, ain't it. Lottie suits you well enough for now. My name is Jacques. French for James — my papa's name. Granny calls me Jackie, but most folks just say, "Play, blind boy." She took the banjo from me and leaned it against the tree. "I can see why they'd have you play but you deserve to be called by your proper name. Jacques. Will you kiss me, Jacques?" Before I had a chance to answer yea or nay (as if) she pulled my mouth to hers and kissed me in a way which surely must have been learnt on distant shores. This did not feel like any Virginia kiss I might've imagined. With her warm and full breast crushed against my chest I could hardly breathe as she lay down beside me under that willow. What happened next is best left to memory — a gentleman, I have learned, does not share his most private actions. I can only say that any fears I had about knowing what to do next got lost in the shuffle — everything fell into place of its own accord — just like playing the banjo. We lay for a time speechless on the bank and then she sat up and began to tidy herself — and me. As she helped me with the buttons on my shirt, she noticed the pouch around my neck. "And what is this, dear Jacques? You don't look like the superstitious type to me. What evils are you warding off?" I grinned sheepishly. "It's a love potion, Lottie." "And you think that's why I'm here with you?" She opened up the pouch and gave it a sniff. "Eeeeeww. This is horrible. I've had a cold, so I didn't smell it until now. If I had, I'd never have come close enough for this." She tossed the pouch into the river. "I read something at the boarding school in a book by this Roman author named Seneca. I think he was quoting Hecato: "I will show you a philtre without potions, without herbs, without any witch's incantation — if you wish to be loved, love." I took her hands in mine and asked with awe, "You can read?" From that moment on, my eyes were opened. We came down to the river every time we got the chance and she read to me: Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift, Sterne's Tristram Shandy, Fielding, Defoe, Voltaire. A wondrous beginning to what has been a long and joyous life stoked with the healing energy of words. She secretly taught Granny how to read and for many years the dear woman read to me from the books Lottie gave her — the Bible and the Compleat Works of William Shakespeare. Many women have chosen to be my readers since and each has brought her own unique spin to the experience — but what man doesn't hold a special place in his heart for his first?

Fishing for Love first appeared in the January 2002 edition of Tonya Judy's Flush Fiction Magazine. [ fandango virtual | morpheus arms | bcc | fv books ] |