|

|

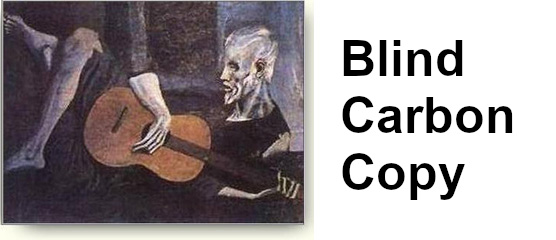

1807 by Blind Carbon Copy Granny told me not mourn her none when she passed on, but no matter how hard I wanted to follow her wishes, the bottom fell out of my world when she left. The days lost their meaning and I suffocated in the endless quiet of the night. Lottie had long since married and moved to Boston and there was no one else around who could read to me. Mr Jefferson assured me that I would always have a home at Monticello, though my blindness, as far as I could see, made me useless to him in the practical sense. I did get the hang of digging his flower gardens and was never short of energy to play my banjo or one of the fiddles to entertain the household but I just wasn't happy. One day back in '96 after he had freed Papa, he told me I was free, too — but freedom is not something a seven year old can understand. In fact, I'm not sure I've got the hang of it now. I think he always carried some guilt for papa's suicide so he was probably concerned about how I'd fair with Granny out of the picture. So anyway, when I tell him I'd like to see England, he offers to stake me. He makes arrangements for my passage with the captain of L'Insouciance, which is about to embark on a voyage from Norfolk, Virginia to England and gives me a letter addressed to a gentleman in Liverpool who can help me get settled. Everything I own, including Granny's bible and the Shakespeare, fits into a knapsack which I carry on my back along with my banjo. Because of Mama, it pleases me that folks say the ship is a French vessel, though it was commandeered for service by the British a few years before. That doesn't seem such a strange thing — everyone and everything I know has been commandeered for service in one way or another. It's not a big ship — the crew is made up of the captain, two mates, 21 seamen, five boys and three idlers — a strange word, since they never are — they take turns as cook, carpenter, surgeon, purser, sailmaker or engineer as needed. The cargo is mostly Virginia cotton and Carolina rice and the manifest includes a number of passengers beside myself including a wealthy young Scotsman with whom I am to share quarters for the next six weeks or so. The first day aboard is a blur of confusion but on waking the next morning I carefully pace off the ship's decks, drawing a mental picture which helps me find my bearings straight away. The upper deck is about 50 paces between the forecastle (sounds like foxhole ) and the poop-deck (20 and 15 paces respectively) and 15 paces in breadth The lower deck is 70 paces, but I hardly go below. The supplies are stored there along with smaller lots of cargo and passengers' belongings and the bulk of the cargo is in the hold. There are three masts growing out of the deck like huge trees. It is from these that the sails are rigged capturing the wind to carry us forth. I'm told to stay clear of the ship's workings and the men when they are busy, but I poke around and gather as much knowledge as my senses will allow when the decks are clear. The sails are made of very thick canvas — I remember how the sheets billowed in the breeze when Granny hung out the laundry and now stand in awe of the engineering that went into the construction and operation of this vessel and the skill of the men who put her through its paces to harness the wind's power. The captain, his mates and other passengers are berthed in the cabins on each side of a big room, the salon, under the poop-deck (that's at the back of the ship, which I will come to know as the stern). The rest of the crew bunk in hammocks in the forecastle at the front or prow. I was grateful for the cupboard that's supposed to be my bunk after venturing into the crew's quarters where the smell of sweaty bodies overwhelms me. Later, when the weather is calm, I take every opportunity to sleep on deck in the fresh sea air alone with my thoughts. The ship itself becomes my hammock, gently cradling me in slumber. From time to time a wave will wake me enough to wonder where I am until the gentle lapping lulls me again to peace. Though my passage has been paid and there is no demand for my efforts, I find the days pass more quickly if I have something to do. My nose usually leads me to the galley where the cook is happy to pass on some of the chores he feels I can handle. His company is good — I could listen to his accent all day and my own voice soon takes on some of the broad character of his speech. The main meal is at noon and consists generally of salt beef or pork which the cook boils in a huge cauldron where all the meals are cooked. On alternating days we eat pease porridge or oatmeal, sometimes with cheese, and every day our allotment of ship bread (hard tack) and a ration of rum. Nobody goes hungry but I come to miss the healthy spread of food provided daily at Monticello, especially the fresh fruits and vegetables, hot biscuits and grits with red-eye gravy. When the work in the galley is done, I take my banjo topside where I play and sing songs of many colors. New lyrics come to mind and the crew enjoys adding their own spicy verses about their women of all kinds. By nightfall, the wind picks up and sometimes the rains come and the sea rises so high it's hard to keep my footing. My cabin mate, Ian Mackie, seems more worried about me than I am — he never gets used to the fact that day and night are the same to me in terms of visibility and that I could make my way around, even in a thick fog. I am surprised to find the crew in such good spirits and looking forward to the wonderful place, this Liverpool, they all speak of with such gusto. When I chance on one or more of them at their work, they are always trading tales, laughing or singing. I'd heard stories from some of the folks back home about life on the sea and the horrors of the slave trading vessels which brought their folks to America. I never forget those stories but on this trip the reality is so different they fall to the back of my mind while the excitement of what is to come keeps my curiosity alive. Ian has an expensive education to back up the steady flow of opinions from his mouth. He loves words and the sound of his own voice. He is pleased to find that I know some of the books he's read and wants to discuss the underlying meanings, the politics and cultural settings — I just want to hear the words and wonder at the magic of the language and tales being told. He's a poet, suffering some as he finds it harder and harder to write. That's why he's returning to Scotland — during his two years in Maryland he was unable to write a single poem. I smile and continue to pluck softly as he rambles on. You never had any trouble writing a song, then, Jacques? Well, no, I say. Course, I don't write — not so it's there for all time. But I never tried to make up a song. They always just come when I need them, that's the way of it. And if it's a good one, sometimes I remember it for later — and maybe it will come out some different than before. But you must give some thought to the metre — how the words work with the music and all. Well, the music comes. It just burns through to my fingers and the words get all lined up with it on their own. Maybe the words and music come together when I'm feeling a certain way. But I don't try to play, dah-dah-dah-dah and think what words go with that sound. Do you, then, with your poetry — do you try to make the words come out in a certain way? Of course I do — now listen to your Shakespeare. Metre is everything, what makes it come alive. And look at his sonnets — they all have a certain pattern of rhyme schemes and beats. Can't you just say what you feel? I m thinking this Shakespeare fella had a natural instinct for it — that he loved to play with the sounds and meanings and he had a good imagination. Somehow how he felt connected with all the beautiful words he'd collected and he had a knack for making them all work together to say what he wanted. But if his genius flowed so smoothly, how do you explain all the sonnets he wrote in that particular form? Well, to tell you the truth, I never cared that much for them sonnets, but if you love someone, won't it come out one way or another? Maybe it's like baking bread — there's nothing says a loaf has to be a certain size or shape, but once you've collected a set of pans, you learn to fit what you do into that form. He found something that worked — people liked them, so he made more. I leave him alone and go topside to find a quiet place to sleep. In the morning, he finds me in the galley with Cookie. Listen to this, Jacques:

thoughts of words plague me as I navigate without a chart through dark waters words which once suckled me like wetnurses hawking warm and supple breasts have transformed themselves into demonwhores pledged to turn my pockets for a wee tickle words which once danced wild fandangos on my pages now gaze at me coyly from another's arms as I hum desperately straining to recall the lyric that was once our song below deck are bulkheads stacked with crewmen in the arms of Morpheus would that I, too could climb the rigging run a line to swab the forward deck neck baking in the afternoon sun draw honest sweat to swap for six sweet hours of sleep these bunks are barely big enough for one comfort means nothing to their hostages dead the moment they tie in with or without the ration of rum but I cannae lie in that emptiness — remembering those fickle wenches who left me alone what might as well be a million miles from anything that looks or feels tastes or smells like home Cookie laughs out loud and stirs his pot. I shake my head. Is this a poem you've written, Ian? I m happy that your dry spell is broken, but I don t understand it. Is it about women? I hear all the ship words but women are supposed to be bad luck on a ship. What's a demonwhore? Who's this Morpheus fellow? And the biggest curiosity — it's got no rhythm to it at all — at least none I can hear. Don t you see, Jacques? It's not really about women — it's about words. It's about not being able to write poetry. The women are metaphors as are the ship references. A metaphor is a figure of speech — your friend Shakespeare used them — All the world's a stage. See, the words which once held the position of mother for me have now turned on me. We were talking about selling out to form last night and I realised that the words had become my whores — I had lost the purity of love I once had for them. Morpheus is the god of dreams in Ovid's Metamorphosis. The arms of Morpheus is a metaphor for sleep. But what's a whore? I ask. Cookie is now laughing so hard he has to sit down. Surely, you know that, mate! A whore is a woman who gets paid for performing sexual services and well worth it, too: a tart, hooker, harlot, prostitute, strumpet, courtesan, a lady of the night. Have you never visited a brothel? You aren't a virgin are you, Jacques? I blush. Ian, there are some things a man doesn't talk about, but I've never found the need to pay for the kind of services you refer to. I've never known a woman who would ask such a thing. But then, I haven't known that many women. Well, my friend — you'd be surprised how many women there are in the oldest profession. Surprised you didn t pick up on these stories in the Bible. I laugh. Granny is the one who read to me from the Bible — I doubt she would have passed on such stories. Well, Cookie, looks like we are going to have to introduce Mr Hemings to the softer vices when we hit Liverpool. Is that pot about ready, then? I'm starved. Now I'm sorry I don't have more excitement for you, but the next six weeks passed much like any other six weeks with the voyage being mostly uneventful: no bad storms, no illness, no dramatic acts of piracy at sea. Perhaps the music and poetry made the days pass quickly. When it came closer to the time for our arrival, Ian turned to the subject of my clothes. I hadn't brought much — one coat, two osnabrug shirts, a waistcoat, breeches, two pairs of stockings and my shoes. I washed the shirts and stockings I wasn't wearing when they started to smell bad. I couldn't see being bogged down by possessions. Ian, however, had a few trunks full of clothing in the below decks and set about to make me more presentable for social situations. I'm slightly taller and thinner, but he is able to find several shirts, two pairs of knee britches, silk stockings, a tweed waistcoat, a warmer coat and various other accessories like handkerchiefs and cravats. I m hesitant to take these from him, but he assures me that he has far more than he could ever use. On this trip my beard is starting to come in for the first time, but I decline the offer of a razor — the idea of growing a beard and moustache appeals to me. He also convinces me that I should not volunteer the information that I m a freedman. I keep the papers in the back of the bible for safekeeping, but never again have cause to remove them. I can't believe how much my life has changed in the past two months and will always be grateful to Mr Jefferson for giving me the opportunity to grow in this way. Liverpool is like nothing I could have imagined, even after having heard so many stories set in English cities. Until you experience the noises and smells of a big city for yourself, you just can't believe it. The first thing Ian does is secure rooms for us in a boarding house. The second thing is to find a pub where we have a wonderful meal of deep-fried haddock, potatoes sliced thick and cooked to just short of crisp, washed down with several pints of ale. Lastly, after much conversation which begins to get fuzzy around the edges, we take a hansom cab to a house which is filled with laughter and smells deliciously of incense and perfumed skin. We are met at the door by a woman Ian calls Madam, though I never catch her surname. She has a deep voice that drips with warmth and before I know what's happening, Ian is counting out coins and I find myself in a room with a young woman convincing me I'll be more comfortable with fewer clothes. The room is warm enough, even without the ale, and I oblige her hospitality in all the ways she suggests. She smells of lavender and freshly ironed linen. Her skin is soft and her voice soothes me as she kisses my eyes, obviously disappointed that I cannot see her beauty. Yes, demonwhore, I think. Oh, yes! And then I ask her to read to me. She laughs. Read? And just who do you think I am, Mary Bloody Lamb? I dress and wait downstairs for Ian. On the way back to the boarding house he asks if I enjoyed the experience. I say, Thanks, mate. I m grateful for your generosity, but when it comes down to it, money can't buy you love. © Blind Carbon Copy/Carrie Berry 2002 (for teejay) 1807 first appeared in the February 2002 edition of Tonya Judy's Flush Fiction Magazine. [ fandango virtual | morpheus arms | bcc | fv books ] |